Tamara Stefanovich: Notes on the Program

“a grand, fierce bevy of sonatas”

“The best music intends to beguile, and that goes for even Beethoven and Schoenberg at their most ‘serious’; don’t let any academic tell you otherwise.” – Ned Rorem

There is a subtle chemistry or sophistry or deep wisdom or something to crafting a compelling concert program. A recitalist, ensemble, or orchestra director must sort out various elements that will result in a whole that is deeply pleasing to the audience. Those include getting a good balance of tempi, moments of both excitement and repose, respect for time-honored repertory but also modern and contemporary music, and the list goes on. To my eyes and ears, Tamara Stefanovich is a wizard in this realm.

This afternoon, I think, we are going to be delighted and transported across many sonorities and emotions as she traverses a wonderfully uncanny mix of styles, times, nationalities, and the like, all within the framework of sonata form! In particular, she brings a very rarely heard Bach sonata, formally and energetically full of dance, that is a sort of extension beyond mere transcription of another composer’s ideas. Dance continues in three witty sonatas of Scarlatti. Who can ever have enough?! A splendid sonata from Bach’s son, C.P.E., moves us a little later on the musical history timeline. Then, Bartok to end the first half, with his unique harmonic language and driving rhythmic sense.

In the second half, a beguiling largo cantabile from a Soler sonata will get us all comfortable for the monumental third sonata of Hindemith, something never heard before in any of PPI’s prior concerts. I am a nut for Hindemith and hope that all of you will join me in being swept up in his unusual panoply of emotions exhibited in this typically tightly crafted composition. His harmonies will feel new to many ears, but they all relate, ultimately, to good old tonic chords in final cadences, for a final exultation.

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

Sonata nach Reincken (c. 1714)

“It may well be that some composers do not believe in God. All of them, however, believe in Bach.” – Béla Bartók

“It’s as if we watch the young Bach acquiring mastery in stages: First, transcription with the form intact. Second, transcription with freer form. Third, original compositions.” – Evan Shinners

If you are surprised about this Bach sonata, we are in one another’s good company. I had never heard, nor heard of, it until now. Yay for being introduced to more Bach!

Taking inspiration from the composer Adam Reincken (1643–1722), whose original piece for strings and continuo was included in his Hortus Musicus of 1687, Bach transformed a fine work into a keyboard sonata that arguably makes it even greater. By adding counterpoint, syncopation, and brightness, he actually reimagined Reincken’s original. He nearly recomposed the first three movements of the original, then added new movements, but still embraced the traditional four movements of a baroque-period dance suite.

In the Gigue, his expansion of the original was quite liberal. One writer even remarked on it actually being more a “Gigue on a subject by Reincken.” As well, it is nearly twice as long as Reincken’s original because Bach just had to add wonderful explorations (musicologists here would talk of “episodes” and “modulations,” etc.) beyond the many statements of the subject of the original fugue. It makes for a very lively dance!

DOMENICO SCARLATTI

Sonatas

“Show yourself more human than critical, and then your Pleasure will increase.” – Domenico Scarlatti

555 is the number most typically given when talking about how many sonatas Scarlatti wrote. But, that doesn’t begin to say much about their remarkable variety and infinite appeal. Pianists, from early intermediate students through virtuosi, love them and often put a few in recitals. Almost all of them are single movement pieces, mostly in binary form, but sometimes are quite audacious in the use of discords and vigorous rhythms. Some are deeply serious, others are light and almost humorous. We are lucky to get three today.

Born Italian, but engaged as a royal court musician in Spain and Portugal for most of his adult life, he wrote in many musical forms, and the “555” mostly come from his time in Madrid, when he was music master to Princess Maria Barbara, who later became queen of Spain. That story goes on and on, but for us it is perhaps more important to note that only a small number of his compositions were published during his lifetime. Nonetheless, they were well received throughout Europe and were even admired by Charles Burney, the foremost English writer on music in the 18th century.

Tamara has chosen a particularly poignant trio of sonatas for today. Hearing them, you may join the list of some of his notable admirers, among them Bach, Bartók, Clementi, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin, Debussy, Horowitz, Poulenc, Messiaen, and Marc-André Hamelin.

CARL PHILIPP EMANUEL BACH

Sonata (publ. 1744)

“He is the father, and we are the children. Whomsoever denies this is nothing but a scoundrel.” – W. A. Mozart, commenting on C.P.E. as composer and teacher.

Second eldest son of J.S.B. and composer of some 150 sonatas for various instruments, not to mention myriad ensemble works, both sacred and secular, C.P.E. Bach is most often recognized as having a pivotal role in connecting the baroque and classical eras. This is because his music includes dramatic shifts in tonality, greater emotional depth, abrupt changes of mood, and innovative keyboard techniques (remember that the fortepiano was just then supplanting the harpsichord) in contrast with his father’s focus on counterpoint and form. He introduced a simpler, more deliberately melodic style, sometimes called “galant,” to allow more expressiveness, opening the way for what would eventually be a much more “subjective” approach to music. Father and son were each stupendously great composers, but quite different from each other.

Of C.P.E.’s musical style, in 1773, Johann Friedrich Reichardt, then the Austrian ambassador to Prussia, wrote that Bach could “give himself free rein, without regard to the difficulties of execution which were bound to arise.” Of his symphonies, Reichard remarked upon their “original and bold flow of ideas. Hardly has ever a more noble, daring, or humorous musical work issued from the pen of a genius.”

In his keyboard sonatas, C.P.E. combined so many different sound worlds, from the chapel to the opera house, dance hall to the corners of his own speculative musical mind, thereby creating music of striking freshness, originality, and power. Opening with a seemingly improvisatory flourish, across its three movements, the G minor sonata unfolds with his famed unpredictability. Here we have those impetuous mood swings, crazy key changes, sudden stops and starts, and not-quite-resolved cadences that make his music so engaging. Burney, the music historian mentioned above, had something to say about C.P.E.’s sonatas, too: “His flights are not the wild ravings of ignorance or madness, but the effusions of cultivated genius. His pieces . . . will be found, upon a close examination, to be so rich in invention, taste, and learning, that . . . each line of them would furnish more new ideas than can be discovered in a whole page of many other compositions.”

BÉLA BARTÓK

Sonata (1926)

“Folk melodies are the embodiment of an artistic perfection of the highest order; in fact, they are models of the way in which a musical idea can be expressed with utmost perfection in terms of brevity of form and simplicity of means.” – Bartók

A pianist of formidable talent and an exceptionally prolific composer, Bartók wrote music that is quickly recognized for its stretching the limits of the piano to make music rich in mood and character. With frequently stunning dissonances and percussive qualities, with melodies that quite invoke the folk music of his part of the world, it is nearly a compositional school unique unto itself. Piano students know him from the first books of the Mikrokosmos and a few make it through to the last pieces (153 in all!), the stuff of distinguished concert music.

This sonata from 1926, dedicated to his second wife, also a pianist, was his sole venture into this medium. In its first movement, we are swept along variously by pulsing ostinato, strong dissonances, a wide array of rhythmic inventions, then melody that contrasts charmingly with “primitive” dance rhythms. The second, a seeming lament, is filled with strange sounds, distant bells, and ritualistic chants. The return in the ending of the single note that began the movement, leading to an inconclusive chord, makes for a poignant and enigmatic halt.

The third movement/finale opens with a burst of folk dance, the fodder that will supply a marvelous collection of variations on a rondo theme. In the proceedings, we can recognize the sounds of local village musicians with melodies just for group enjoyment. We might think that they are authentic folk tunes, but they are actually sprung from Bartók’s own imaginative invention. Surprising shifts of tempo and surprising interruptions between each new quotation of the theme, building to a brief coda, make for a dramatic conclusion. I only wish that we could serve slivovitz (Hungarian plum brandy) at intermission!

ANTONIO SOLER

Sonata

Best known for his many mostly one-movement sonatas, as, in a way, was his teacher, Domenico Scarlatti, Soler led an unusual life. Entering a monastery when only six years old, to study music, he was appointed to an important musical directorate at only 17. He took holy orders at 23 and embarked upon a busy routine, including writing some 150 keyboard sonatas (among 500 known works), many of which are thought to have been written for his pupils, three of whom were sons of the Spanish King Carlos III.

To my ears, SR 110, as the definitive catalogue calls it, is especially introspective and touching, provoking something akin to the feelings one often can have observing the most important moments in life – seeing a child graduate or get married, moments of reconciliation after an argument – and sensing a hard-to-describe gratitude just for exactly that feeling. Even to our modern ears, it speaks so profoundly in its Iberian melodic sense, vibrant modal harmonies, and sudden modulations, just for dramatic effect. I hope that there might be a little extra silence after the final chord, just before applause.

PAUL HINDEMITH

Sonata (1936)

“There are only two things worth aiming for, good music and a clean conscience.”

“Tonality is a natural force, like gravity.”

(To fellow musicians) “Your task it is, amid confusion, rush, and noise, to grasp the lasting, calm and meaningful, and finding it anew, to hold and treasure it.” – Hindemith

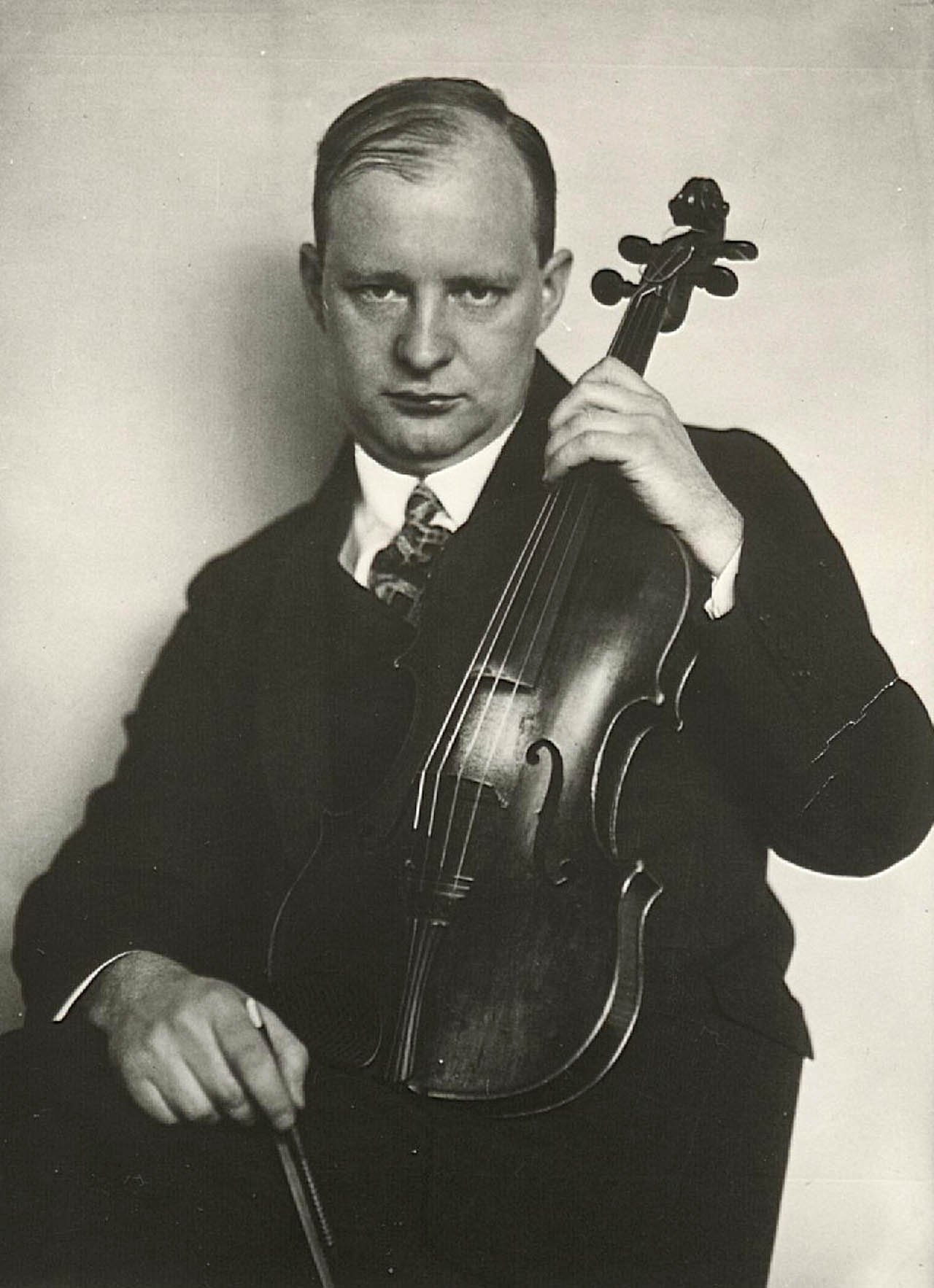

Hindemith’s biography is a fascinating subject as he was one of the most prolific, versatile, and thoughtful musicians of the 20th century. This little essay does not begin to give enough room to really describe him. He was not only a composer, music theorist, teacher, and conductor, but concertized widely as a violist, violinist, and pianist. He was denounced by the Nazis, had to emigrate permanently from his native Germany, then taught some of America’s most important composers and performers. He also created a music school in Turkey, leading the reorganization of Turkish music education. Having become an American citizen in 1946, he returned to Europe in 1953 to teach at the university in Zürich. Winner of myriad prizes for his music, at the awarding of the Balzan Prize in 1962, he was praised “for the wealth, extent, and variety of his work, which is among the most valid in contemporary music, and which contains masterpieces of opera, symphonic, and chamber music.” I hope you might have a chance to learn more about this remarkable man.

But, today we are concerned with his Third Piano Sonata, the third of three, all written in 1936. They came shortly after the completion of his operatic masterpiece, Mathis der Maler (Maler the Painter), at which time his reputation was deteriorating with the Nazi regime as they thought its story to be degenerate. He eventually would have to leave his beloved Berlin. At the same time, though, he published the first of the three volumes of his very important treatise, The Craft of Musical Composition, the whole of which remains fixed in the canon of pedagogical studies for composers, analysts, and performers.

In approaching the third sonata, we will do well to remember that composers in every new era of music have struggled with organizing new ideas formally in order to give coherent shape and integrity to a composition. This involved special challenges in the early 20th century as the key-based, tonal organization that had lasted for hundreds of years in Western music was dissolving. Schoenberg was especially effective in this regard, putting forth his thesis of Serialism or “Twelve-Tone” writing that, for many, freed composers from the strictures of tonal writing. We can agree to disagree about the ultimate results of that influence.

Against the Schoenbergian model, Hindemith proposed something else, which he codified in The Craft, giving new possibilities for tonality. In that brilliant work, he put forth a new way to express traditional ideas of counterpoint and harmony considering all twelve pitches to be of equal weight and potential in the unfolding of a tonal composition, dependent not on keys but on the inherent physical characteristics of sound. It would be a lot to explain, but any listener will note his return to “normal” tonal triads in final cadences. We hear his conviction for dissonance always resolving to consonance. I always find it all thrilling.

Many may think of Prokofiev’s writing when hearing Hindemith’s third sonata. Very virtuosic writing is contained within a classical four movement form, with the “normal” sonata-allegro first movement, then a scherzo, then a slow movement, then, happily, a daredevil finale.

We are beguiled by the lyrical “sicilienne” of the opening movement, albeit perhaps left wondering about the interruptions disturbing the pastorale it means to portray. We get virtuoso pianism in the second movement, something popular in the Russian way of doing piano things in the era, leading to real neo-Romanticism in the third movement. Here is the emotional heart of the whole sonata, having a wide range of dynamics and coloristic contrasts, and a strong emphasis on melody.

A double fugue of immense technical challenge (Tamara will make it seem like a breeze, I’m sure) gives the sonata a brilliant, exuberant conclusion. It is a toccata, too, to my ears, and invites the listener to listen closely to grab each of the entrances of the fugue subjects.

Thus ends this brilliant program built entirely of sonatas. You will agree, I hope, with the tag line I wrote a year ago about this recital: “a grand, fierce bevy of sonatas.”